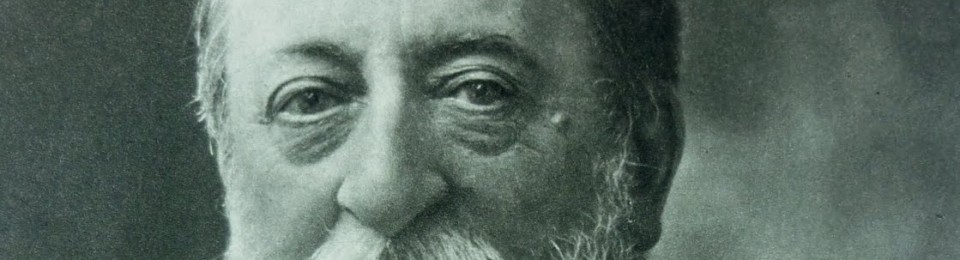

Saint-Saens, it’s fair to say, burned a lot of bridges with other composer during his career – in most cases not to his advantage or credit. Perhaps, in the long term, the most damaging of these incendiary campaigns was that against César Franck, the Belgian born professor of organ at the Paris Conservatoire, influential teacher and winner of ‘best sideburns of the year 1878’. Saint-Saens was at least superficially friendly with Franck initially, before later dropping any pretence of amity. The cause of this falling out was the premiere of Franck’s Piano Quintet in F minor – a piece which is a bit overwrought for my tastes (I prefer my music to be average levels of wroughtness).

Dedicated “to my good friend Camille Saint-Saens”, the Piano Quintet was premiered in 1879 with the dedicatee at the piano1. During the course of the performance Saint-Saens became more and more exasperated, before storming off the stage at the end and refusing to acknowledge the applause or Franck’s thanks. The slighted Franck subsequent kept the dedication but pointedly removed “my good friend” from it. Supposedly, Saint-Saens was aggrieved at what he perceived was a covert picture of a passionate obsession with his pupil Augusta Holmes2, a composer who Saint-Saens also lusted after. But that seems a little weird as an explanation (can music really be that transparent?) – and I imagine it’s more simply that Saint-Saens just really hated the piece and felt insulted that he was its dedicatee3.

For all that Saint-Saens held Franck’s music in disdain, there is one aspect of Franck’s compositional method that it seems Saint-Saens did occasionally adopt, and that is ‘cyclical form’. This doesn’t refer to music that sounds like a rusty pushbike (although some of Franck’s music melodically does have that characteristic), but rather a form of music where the same thematic material is continually reused as the basis for the melodic line in all the movements of a piece – kind of like a theme and variations on steroids. This is not music with a simple call-back to the first movement in the last, like Beethoven’s 9th symphony or Saint-Saens own first piano concerto, rather clear reworking of the same melodic material in different guises.

As a stout conservative in terms of form, I very much doubt whether Saint-Saens would have accepted the characterisation of pieces like the Third Symphony (his famous Organ Symphony) as being Franckian in form – but to my non-professional ear, they sure could be heard that way (certainly in the Organ symphony the final famous chorale like tune on the organ, used to great effect in the film Babe4 can be heard in different, almost unrecognisably subtle, ways throughout the work). Which is how we get to Saint-Saens’ fourth piano concerto – a deeply curious work in that it forgoes large periods of virtuosity (though it is certainly still technically difficult to play) in favour of the development of two principal themes, in a cyclical manner, throughout its half hour.

In many ways the fourth piano concerto is a companion (or a pre-test) for the later third symphony. First off, it’s in the same key (C minor) with a rousing C major finale. Second it’s in two movements – albeit very expanded ones. The first slow, the second fast – but even there, like the organ symphony, each movement can be split into halves – a moderate then slow first movement, then a scherzo-finale second movement.

The concerto starts in a very odd way – almost determined not to give the audience a rousing start. We have the first main theme introduced in the strings only. A very ponderous, slightly sinuous and rhythmically very straightforward theme that is then echoed by the piano playing in simple block chords. The overall feel is of someone trying to sneak into a darkened house late at night without being noticed – which is not a usual atmosphere for the start of a piano concerto where typically the pianist bursts in through the front door and smashes the hall table.

Essentially the rest of the first part of the movement is a set of theme and variations on this “A” tune, with the piano part slowly becoming more animated and complex and building up to the introduction of the whole orchestra in a heavily austere manner (clearly the person sneaking into the house has been caught by their irate partner). Eventually things settle down to the second section, a much more affectionate (slow movement in A flat major that introduces the “B” theme for the work. Again, this is initially a very simple, almost choral-like tune played by the wind interjected by rippling piano effects, but it is slowly developed into a more lushly romantic movement, with arresting chord progressions and some chromatic ‘slinkiness’ in the same mood as the sinuous nature of the main “A” theme. However, the overall feel of the rest of the movement is of a tranquil reverie.

The second movement suddenly kicks us out of the reverie in a ‘hey, what was I talking about?’ manner, before we return to the “A” theme in a much more agitated manner, before the sunlight breaks through into a thematically different scherzo tune in E flat major, that is much more light-hearted.

However, the agitated version of the “A” theme returns, before eventually fading away into a fugal section that reuses some of the slower chromatic material from the slow movement. You sense at this stage that something is building up to a grand finale – and sure enough eventually we have a switch to a lively ¾ time in C major, heralded by a brass fanfare. Before the piano comes in – ultra-simply intoned in just the single line in the right hand – with the final theme – a rhythmically transformed (but melodically identical) version of the “B” theme.

Sure enough, the rest of the concerto works away at this developing this, to be honest for a little too long and repetitively, until the end where at last we get some good old tub-thumping.

Overall the structure and development of the material in this piano concerto sometimes feels quite dry resulting in a work that is a little difficult to warm to (certainly compared to the fun drama of the second piano concerto), but actually the more I listen to it, the more I like it, so perhaps I’ll change my mind more. But, for me it’s a clever and subtle piece rather than a lovable one.

Piano Concerto No. 4 in C minor, Op. 44

Why you might want to listen to it: I think it’s the most unusual of Saint-Saens’ concertos. It’s the musical equivalent of a cryptic crossword

Why you might want to avoid it: it’s difficult to see that you would recommend it as a piece with which to ‘get into’ Saint-Saens. That’s my Franck assessment.

1 It’s worth pointing out that Saint-Saens was sight-reading the part, which is a little disrespectful in my book

2 Franck in later life referred to this obsession in terms (e.g. “her handsome breasts”) which in these modern times sit a little uneasily for a teacher-pupil dynamic – although Holmes remained a close friend with him until his death.

3 I think it is possible to write a piece of music out of spite. I remember, at school, having to arrange some music for someone I disliked and I deliberately made it overly-difficult so they would struggle to play it. Hey, I was a teenager – and the individual went on to be a professional musician, so clearly he had the last laugh.

4 I’m not sure what Saint-Saens would have made of his music being sung by a pig. Although the weird and disturbingly imaginative darkness of Babe 2: Pig in the city might have appealed to him – if you’ve never seen it, it’s one of the oddest sequels to a lovable and heart-warming kids films you’ll ever see. If Mickey Rooney as a mute miserable clown living with an evil orangutan companion is the thing you never knew existed check it out.