What a curious and fascinating work this is. When I began this blog running through the complete works of Saint-Saens one of my stated intentions was to see if I might encounter unexpectedly excellent unknown pieces. It’s works like the Le Déluge which is what I was hoping I might hear.

Written in late 1875 at the time of the birth of his first child, André1, and premiered in 1876, Le Déluge (the Flood) is an oratorio based on the story of Noah’s ark. So far so classical-music-normal. Except, this was a curious choice of form for Saint-Saens and one that it doesn’t seem he was particularly enthusiastic about (he described oratorios as ‘pleonastic’2). The suggestion came from his publisher, who felt that perhaps oratorios might be on the up3. But, in fact oratorios were already viewed as old hat, and nowhere more so than in France. Only in England, probably due to the lingering impact of Handel and Mendelssohn did Oratorios persist, but even there with the increasing reputation for being dominated by syrupy music4 and warbly performances by amateur choral societies.

Of course, Saint-Saens was not averse to retrograde classic forms, and as a young man he had written a Christmas Oratorio (one of my favourite of his works), so I think he must have spotted an opportunity here to apply a mixture of strict classicism and modern romanticism – but what a weird mix it is. Indeed it was too weird a mix for the audience at the first performance where the middle section, which portrays the actual flood itself, was greeted by catcalls, jeers and disruption (sufficiently so that the conductor stopped the performance and started it again from scratch)5. To me, though, this strange and colourful combination of styles is what makes the work enormously fun to listen to.

It’s not a long work (oratorio-wise) being only 45 minutes-or-so long, but is divided into three highly contrasting sections – the first representing the world prior to the flood with God indicating that he’s mega-pissed. The second is the flood itself, and the third the represents the dove being released from the ark and God doing the old ‘oops sorry about that’ routine with a final chorus of ‘isn’t life wonderful and let’s not worry too much complete-planetary-obliteration-of-most-organismal-life thing’.

Section 1 is remarkably quiet and gentle, being scored for soloists, choir and a string orchestra (with harp) only. Saint-Saens actually, I would argue, shows great taste with this section because it must have been tempting to play up the ‘evil of humanity and God’s anger’ thing to a more dramatic extent – but by doing so he augments the impact of the actual flood in the second section itself.

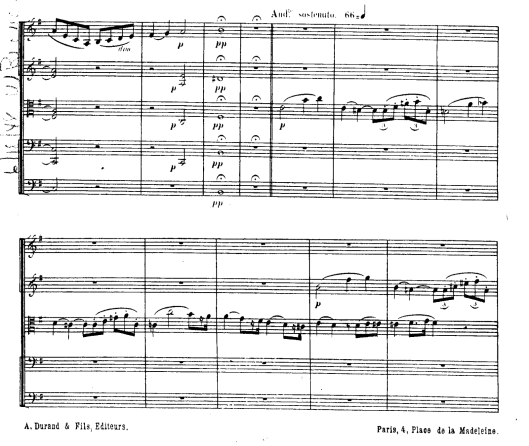

We begin with a prelude that starts out with some austere chords and then proceeds into a fugue on a sombre Bach-like theme.

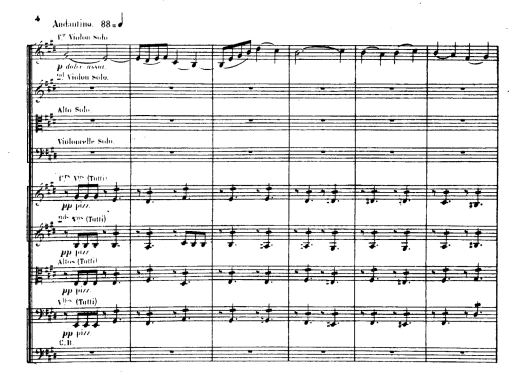

It’s again an odd choice – but here I think some interesting insight is offered into Saint-Saens’ intentions by what he told the orchestra during rehearsal for the first performance where he instructed the strings to play absolutely without any vibrato or rubato in order to represent God alone, bored and brooding. The fugue dies away and is replaced by a lovely theme representing Noah – given to a violin solo over pizzicato strings. It’s very sweet and is probably the reason why the prelude is the one part of this work that is still occasionally played.

Eventually the singers enter with recitatives (often accompanied by solo harp) describing the world and God’s dissatisfaction. There are other snatches of fugue on even more austere themes (albeit more upbeat), that show Saint-Saens facility with counterpoint, though perhaps do sometimes feel like an exercise of going through the motions rather than tight drama. There are also occasional snatches of chorale tunes, which become more of a feature later in the work.

With part 2, the music opens up into a full orchestra complete with a terrifying brass section including the rare appearance of saxhorns (previously used by Saint-Saens in his first symphony). Here we have perhaps one of the most avant-garde pieces of music Saint-Saens wrote, much more of a romantic tone picture with chorus, depicting the rain and the wind picking up through tremolo strings and trills, and chromatic sinuosities the winds, and Wagnerian horn calls that sound positively sinister. The orchestra crescendos with the choir joining in – then comes the storm of the flood itself – with crashing cymbals and gongs. There isn’t really a melodical theme running through this – it’s all painting – not dissimilar to film music – but I found remarkable is the later part when there is a progressively ascending chromatic scale in the orchestral that lasts way beyond when I would have expected to end. It’s quite remarkable – and I guarantee if you played this to someone they would not pick it as Saint-Saens. During the ascending chromatic scale the music dies away representing the subsiding of the flood waters and leaving us with the remains of destruction.

The third part can’t really live up to this, and is more conventional, reducing the orchestra back down to classical dimensions. Here we now have a working of a chorale theme that forms the first part of the music here, and that appears throughout the rest of the movement – essentially the music of ‘thank God we survived’6.

We also see the reappearance of Noah’s theme from the first section, and a second chorale theme that is more bold and celebratory. The soloists and choir are slowly introduced and build up ultimately to a final fugue, based on actually a fairly weak theme.

It all finishes fairly conventionally after this point, in ‘final chorus of oratorio’ style – satisfyingly and everybody singing. It should bring the roof down (if the rain hasn’t already done so).

Le Déluge

Why you should listen to it: This is not a boring work – but particularly put the second section on full volume in your living room. Heavy metal music. And that is not a word that applies to Saint-Saens often (if at all in any of his other music).

Why you might want to avoid it: If fugues are your ideas of a musical rainy day, then you get a flood of ‘em here7.

1 Neither of his children survived past early childhood, something I’ll discuss at

2 Yes, I had to look the word up too – to save you the bother it means ‘using more words than is necessary’.

3 Proving that you shouldn’t listen to publishers

4 Even I can recall a time that works like Stainer’s Crucifixion from 1887 were regularly performed, a work that gave rise to the famous piece of graffiti on the wall of the Royal College of Music in London “What do you think of Stainer’s Crucifixion? It sounds like a good idea”

5 I’m never certain if composers revel in this or not? I mean, I get that a huge ovation is the preferred response, but I mean isn’t this kind of ‘throw the furniture’ response better than a politely bored 20-second ripple of applause?

6 Though perhaps thanking God might be a bit ironic.

7 See what I did there?

Pingback: Samson et Dalila, Op. 47 | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens