If there’s a form of music that doesn’t get enough love I think it’s the piano quartet – not four pianos1 – rather piano, violin, viola and cello. There are whole competitions for piano trios and string quartets, but never, it seems, one for the piano quartet. A composer friend of mine, Andrew Anderson, indeed thought the same and tried to establish such a competition here in Australia, ultimately unsuccessfully (however his two rather excellent2 contributions to the genre have been recorded and are available on spotify and youtube. What is it though that makes the piano quartet supposedly less viable? Is it, dare we whisper it, the presence of a ….. viola?3

Back in my university days I actually played in a piano quartet group, and we were invited to play at a musical soirée to a group of dignitaries, including the then Chancellor of the Exchequer in the UK (the chief finance minister) – a fairly affable individual (though his political affiliations were not aligned to mine) who I remember lamenting the fact that since he had become Chancellor he no longer could spend whole nights in Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Bar in London (too much work), which he had regularly done as a junior minister. The other thing I remember him, rather more startlingly (given he was the second most important politician in the UK at the time), was being involved in a conversation with him about holidays and how he hated going to the beach because ‘all you do is end up with sand in your pork’.

Anyway, we played, at the evening, the Mendelssohn Piano Quartet in B minor, an early work, that has some unusual piano writing in parts (essentially the piano just plays single notes that complete the harmony, but can sound like the pianist is just picking random notes out of the air) that completely confused the first violin in the strange acoustic (a heavily carpeted drawing room) we were in. (“What the f**k were you playing?” I remember him asking afterwards).

There are actually plenty of excellent examples of piano quartets by the ‘biggie’ composers – Mozart, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Schumann for starters, and to these excellent contributions I would add Saint-Saens’s 1875 Piano Quartet in B flat major – not, actually, his first piano quartet as there is a youthful piano quartet which was fine but perhaps a bit more formulaic.

Saint-Saens also felt that the piano quartet did not get much love, hence his proposal in late 1874 to the Societé Nationale, that they programme more such quartets – and his putting his money (or at least his compositional talents) where his mouth was and premiering the quartet in March 1875.

Another proposal from Saint-Saens’ that bore fruit in early 1875 was altogether less admirable and well-fated – his short-lived marriage to Marie Truffot. His junior by more than 20 years (she being barely 19), they were spectacularly poorly-matched – not just because of age (although she was a keen music-lover), but in temperament, with Saint-Saens being a essentially a starchy and prickly misogynist, and her being fairly innocent and (one gets the possible unfair impression) quietly dull. As we will eventually come to, he treated her appallingly, but initially there seem to have been mildly good terms between them, sufficiently so that he would play here his latest compositions and ask for comments. So, one imagines, that the piano quartet must have been one such piece, premièred, as it was, just a month after their marriage.

The piano quartet itself is an unusual work in construction and feel. Although comprised of four movements in a nominally ordinary structure Fast-slow-fast-fast – the key signatures are unusual in being, after the first movement, totally in the minor key. B flat major – G minor – D minor and then D minor again (only returning to B flat major towards the end). Further, the first movement is a tranquil and gentle moderate pace – almost feeling like time is standing still in places – but the three remaining movements are fiery, and highly rhythmic. Were it not for the fact that the fourth movement explicitly reincorporates and repeats melodic material from the first two movements, one might not imagine that the movements represent a cohesive work.

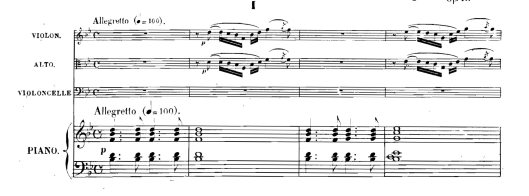

The first movement starts with the piano gently starting with B flat major chords and the violin and viola an arpegiatted figure that ends with a slightly skippy syncopated figure that reoccurs throughout the whole movement in different forms.

The melodic material is switched around between strings and piano and developed leading to a second melody that is rather lovely and built up in a way a bit reminiscent of the introduction of the Mozart Quintet for Piano and Winds, with the same descending figure building up on top of each other in each of the instruments with increasing lush harmonization.

It’s beautiful piece of writing. Most of the rest of the movement develops these two pieces of material, but the overall feel is one of calm.

The ‘slow’ movement could hardly be more of a contrast. It starts loud and spiky with the piano stomping along in staccato chords, before the unison strings come in with a sombre chorale.

The overall feel is one of a grumpy schoolmaster forcing his unfortunate class to recite dull poetry. To be honest, as interesting and refreshing as the contrast is to the first movement, the mood outstays its welcome, in the way that one does tend to get fed up with grumpy individuals. “Dude, just lighten up” was my feeling after several minutes of this.

The third movement is a more Mendlessohn-ian like light scherzo which has a curious skipping motif in the second and further bars that almost subconsciously harkens back to the syncopated figure from the first movement.

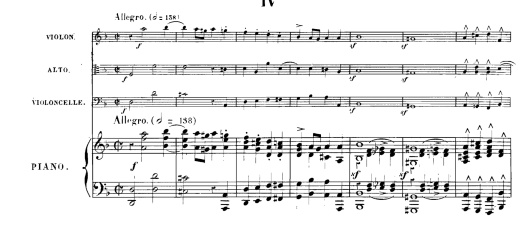

The movement develops in a fairly standard fashion with louder diversions into B flat major and then a couple of curious recitative like cadenzas where the violin and piano get to hold up proceeding and sound very dramatic and dark4. There’s a prestissimo cadenza which bring the movement to a quite zephyr-like conclusion before we plunge in, in the same key into the fiery and severe start to the last movement..

This severe mood, reminiscent of the second movement is developed with chromatic off-beat notes for quite some time, before the music ultimately dies away and, like a faint indicator of a sunrise and change of mood, the chorale tune from appears pp and now in E flat major in the strings. The fiery main tune tries to re-establish control, but the now soft-and-gentle chorale in the strings re-appears leading to the piano reintroducing the first movement’s syncopated figure. Almost like a desperate raging, there is one more attempt to maintain the fiery mood – but it dies away more quickly, before we finally return to the two melodies of the first movement, and then, the main tune of the last movement is converted into an altogether happy B flat major version, and then interwoven in a brilliant piece of contrapuntal writing with the second theme from the first movement, and the chorale tune. It’s an exhilarating ending that shows off Saint-Saens skill as a composer. Definitely worth listening to in ‘score-o-vision’ – although I would grumble in the recording below that the pianist has a fairly lax attitude to ‘staccato’ (it sounds pretty legato to me, which made me almost as grumpy as the schoolmaster in the second movement).

Piano Quartet in B flat major Op. 41

Why you should listen to it: It’s arguably Saint-Saens best piece of chamber music. Hugely varied, and technically brilliantly written.

Why you might want to avoid it: Piano Quartets…. Pfff… not much to them is there?

1 Though there is a remarkable arrangement of Rossini’s Semiramide overture for 8 pianos and 32 hands (two players on each piano) by Carl Czerny that is worth a listen

2 Yes, ok, I may be biased but there are other reviews out there of these works that rate them very highly

3 Viola player joke: How do you get a violist to play 32 demi-semiquavers in a bar? A: Write a semibreve (whole note) and mark it ‘solo’.

4 Violinists love that kind of thing. Violists, not so much.

Pingback: Greatest Hits of the 1870s | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens