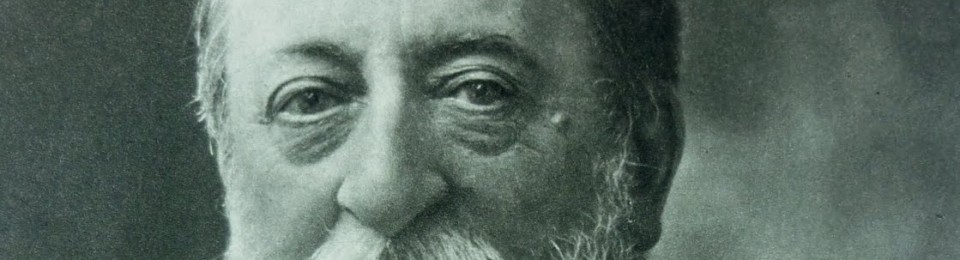

Inspiration is an elusive beast. I remember seeing an interview with film composer John Williams, who talked about his work ethic and said words to the effect of “if you wait around as a composer waiting for inspiration to hit you, you will be waiting a long time”. Consequently, for, Saint-Saens who claimed that he was like an apple tree when it came to composition1, I doubt whether inspiration was actually something he thought too hard about. For a jobbing artist, you just get on and write something.

At present I’m working my way through the collected books of John Christopher (aka Sam Youd – his real name, Hilary Ford and several other names), best known for his teen-aimed science fiction, particularly the excellent Tripods series of books, which were a favourite of mine as a young lad. Is he an inspiring writer? No, but he wrote a lot in a very enjoyable and page-turning John Wyndham (Day of the Triffids) style. And he wrote a lot (averaging 4 novels a year, apparently).

It must be great to just easily sit down and write away (regular followers of this blog will appreciate that that is not my strength). But, consequently, to expect every output to be inspired and a masterpiece is unfair. So, we come, in a round-about way to La Jeunesse d’Hercule (The Youth of Hercules) – the last of Saint-Saens’ symphonic poems all written in the 1870s and the most that is obviously inspired by the Liszt-ian archetype of symphonic poems. Written in 1877, it depicts the story of the youthful Hercules and how various bacchanalian forces (read women) attempt to corrupt him, but he wins out and remains pure. The piece was written in the early years of his spectacularly-poorly-judged marriage to Marie-Laure Truffot, the younger sister of one his pupils, some 20 years his junior (he married at the age of 39). This was the only piece that he ever dedicated to her, and she refused the dedication (perhaps because of whole underlying ‘I am pure, and you will not corrupt me, vile woman’ vibe). However, with what was to come in the next year, this was positively the best time in their marriage, with two young sons born in 1876 and 1877.

Written for standard orchestra with a bit of extra colour from the harp and some percussion, the work starts with a slow quiet E flat major introduction in the violins, somewhat reminiscent of the old Nat King Cole song, Mona Lisa.

Things then settle down into the main opening theme, again just in strings – in 4/4 and pretty humdrum, if a little chromatic in the harmonisation. I’m not quite sure how this represents Hercules youth, except that it sounds like it must have been quite boring.

A second theme, now in 9/8 and in D major (then E major), apparently representing Hercules’ purity (doesn’t that just rankle you?) enters in the wind, and is played around with in a bit more of an interesting fashion.

Then comes the temptation section, starting quite intriguingly in the flutes over hushed strings….

….before building up into a full-blown orchestral orgy (or should that be an ‘orchy’?). It’s the best part of the piece in terms of colour, with prominent roles for the piccolo, brass and more percussion than you can shake a stick at3. However, even so, it’s kind of like a less interesting version of Night on the Bare Mountain, and the Bacchanale from Samson and Delila, completed in the same year, leaves it completely in the dust.

After that the corrupt festivities abrupt stop and we return to the original ‘purity’ material, dealt with in various ways (fugue, overlaying of themes) that is academically clever but a bit dry. The loud coda strives for grand majesty, but is just ploddingly loud.

As you can tell from my wording above, La Jeunesse d’Hercule is not great Saint-Saens. It is a turgid 17 minutes, far longer than any of his other symphonic poems, and feels longer. As ever it’s well-orchestrated, but it is massively lacking in any compelling melodic material4. In the slow sections, the strings often seem to be ambling around with no clear direction, just padding out the piece, and even the central bacchanale section feels a bit cheap and uninteresting – heartless fireworks. I find it interesting that Saint-Saens clearly liked it enough to regularly programme it as a visiting conductor right into old age, and indeed proposed it as the piece for his 1893 doctoral graduation at Cambridge University (in the same ceremony as Tchaikovsky and Bruch), only for Charles Stanford, then head of the Cambridge University Music Society, to decline it, saying it was too long, even though Tchaikovsky was programmed with his Francesca da Rimini symphonic poem (which is 24 minutes long). Burn.

La Jeunesse D’Hercule Op. 50

Why you might want to listen to it: For completists of Saint-Saens’ orchestral works, this will fill out your collection in the way that reading The Little People will fill out my John Christopher collection5.

Why you might want to avoid it: This is the piece that at least makes you think that perhaps S-S made the right decision in not writing any other symphonic poems.

1 Meaning that he produced music in the same way that an apple tree produces apples – they naturally just grow off the tree – rather than infested with wasps.

2 I can particularly recommend A Wrinkle in the Skin, about an earthquake-induced post-apocalyptic landscape, and Cloud on Silver – which is like an adult version of Lord of the Flies or Lost.

3 Given this involves a triangle, bass drum, timpani and cymbal, I estimated you need to shake at least five sticks at this percussion – although curiously Saint-Saens specifies that the cymbal be hit at first with a bread-stick

4 So, basically exactly like most Liszt tone poems.

5 I still want to read The Little People, but it is about Nazi leprechauns, so I’m…. trepidatious that it might not be great quality.

Pingback: Greatest Hits of the 1870s | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens