I was always told by my music teachers at school that the French Horn is the hardest instrument to master. This was an impression brought home to me with ear-bashing reality when our school’s best horn player managed to fluff the relatively simple, but crucial, solo horn entry in the slow movement of Shostakovich’s second piano concerto. For perspective this consists of a single held note, which the horn player singularly failed to hit until about the seventh attempt1.

Bear in mind, then, that the modern French Horn (which as Dave Barber points out in his estimable Musician’s Dictionary – is actually German, not French2), is a considerably easier instrument to play than the traditional natural horn used until the mid-19th century. The modern horn, you see, has valves (as most modern brass instruments save for trombones do). These can rapidly alter the air-flow through the instrument, giving it a much greater capacity to hit the notes that traditional horn players can only achieve through a combination of amazing embouchure, craftily placed hands, and ritual sacrifice to the brass gods. With the natural horn the only way to modulate the basic pitch of the instrument is to employ different ‘crooks’3 – a complicated procedure that can only realistically be done between movements or suitable long rests.

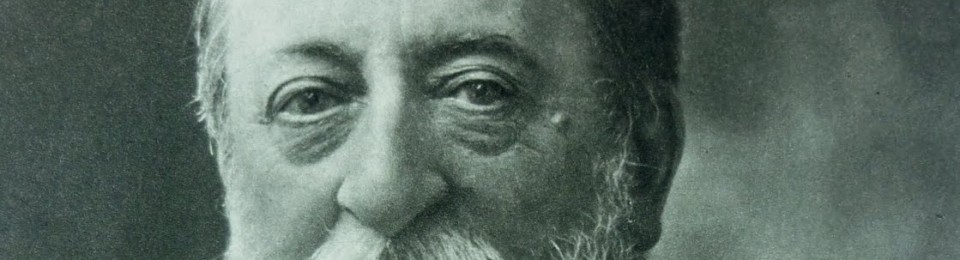

By 1874, the year that Saint-Saens wrote the first of his two romances for horn and orchestra, the natural horn was going the way of the dinosaurs. The valved horn had been introduced in France in 1839, but strangely (given it would later be called the French Horn) met great resistance to the new-fangled instrument. I suppose some dubiousness over a new version of a classic instrument is inevitable – think how you feel when somebody says they’d like to play the electric violin for you – but you would have thought that the advantages of the valved horn in terms of the versatility to actually play chromatic scales, for example, would have soon outweighed any aesthetic preference for the sound of the natural horn. Not so in France where most horn players continued to plough on with natural horn, and where the experts in the conservatoires refused to countenance anybody playing the young upstart instrument. One such expert was Henri Garigue (sometimes credited as Henri-Jean or Jean-Henri Guarigue), one of France’s leading horn players in the late 19th century.

One thing that the horn, natural or otherwise, lacked was a substantial back catalogue of concertante works. Sure there’s the big four Mozart concertos, a couple of Haydn ones (almost never played) and even the odd Weber concertino (odd in the sense that it calls for the horn player to play a 4 note chord by singing down the instrument and creating resonant harmonies). Frequently, then, horn players would adapt other works for the instrument, if only to give them something to do when they weren’t ritual sacrificing things.

So, when Garigue asked Saint-Saens for a short piece for him to play with a salon orchestra (and the forces for this romance are very modest, just strings, and six woodwind instruments (2 flutes, 1 oboe, 2 clarinets and 1 bassoon), Saint-Saens readily complied. The Romance is not technically demanding or virtuosic (and indeed when played on modern French horn is often set as an examination piece for the lower grades), but really tries to exploit the timbres of the natural instrument – as is demonstrated in the excellent youtube video below.

This kind of piece shows, to me, the best of Saint-Saens in not over-thinking things and writing just a very elegant melody with uncomplicated accompaniment. Clocking in at a touch under 5 minutes the Romance is in simple binary form, with a gentle but slightly noble opening theme that perfectly fits the sound of a horn, accompanied by a gently rocking string accompaniment in F major. There are no unusual or unexpected modulations, but the sound world is just instantly appealing.

Other instruments (notably a solo oboe) occasionally appear, and the middle section is slightly more urgent, but it quickly dies back down to the original theme which is simply repeated with a tiny 4 bar coda to round it out. I’m sure it’s the kind of piece Saint-Saens would have written in an evening, but I’ve never been one to believe that you can’t write great music quickly. With this piece for natural horn, Saint-Saens shows off his natural ability for crafting beauty out of the simplest material.

As for Henri Garigue, his advocacy for the natural horn lasted until 1890, when, in a startling turn of events, his son was barred from the Paris Conservatoire for daring to play the valved horn at an audition. So incensed was Garigue, that, out of solidarity for his son, he abandoned the natural horn and, literally, wrote the textbook on modern horn playing using valved horns.

Version with modern horn and orchestra…

Version with natural horn and piano (with fascinating introduction on how natural horn playing works)…

Romance for Horn and Orchestra Op. 36

Why you might want to listen to it: It sounds equally beautiful on the valved horn or the original instrument – but it’s a fascinating example of one of Saint-Saens concertante works that is basically (and unfairly) unknown – except to horn players

Why you might want to avoid it: You’ve got to listen to my old school orchestra horn player attempt it.

1 Which does also brings to mind the classic viola player joke of “How do you get a violist to play 32 demi-semiquavers (32nd notes)? Write a semibreve (a whole note) and mark it ‘solo’”.

2 and not to be confused with the English Horn, which is French…. and not a horn.

3 in this case a separate tube attachment, not a member of the criminal underworld.

Pingback: Romance in D for Cello and Piano, Op. 51 | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens

Pingback: Greatest Hits of the 1870s | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens