***UPDATED*** I initially missed a whole chunk of text when I copied this across – now it hopefully makes a bit more sense

What is it with spinning wheels and fairy tales? For an item of mundane household equipment, they sure have a bad reputation. Think of the tale of the Sleeping Beauty and the way she pricks her finger on a spinning wheel on her 16th birthday and falls into a deep sleep. Or the female protagonist in Rumpelstiltskin whose must spin wool into gold in order to marry the king, or else have her head chopped off1.

I can remember finding spinning wheels fascinating as a young child because a kindergarten teacher had an old-fashioned spinning wheel and brought it in to school to show us. I watched agog as Miss Mottram made the spindle turn back and forth with the lurch of the pedals, as the wheel span around. And then was of course immensely disappointed that Miss Mottram could not actually spin gold2.

There’s no doubt a PhD thesis that could be written about the symbolism of spinning wheels in folklore, and indeed there’s plenty of dissection of this on the web, such as this post from The Willow Web which identifies what the spinning wheel represents – be it sexual awakening in Sleeping Beauty (viz. the curiosity surrounding that which is forbidden by the father, not to mention the involvement of blood), to the neverending and impossible task of the maid in Rumpelstiltskin. In the latter context, spinning is a hugely mundane and time-consuming task, undertaken only by women (naturally), and those women without other family responsibilities at that (there’s a reason why unmarried women were called ‘spinsters’)3.

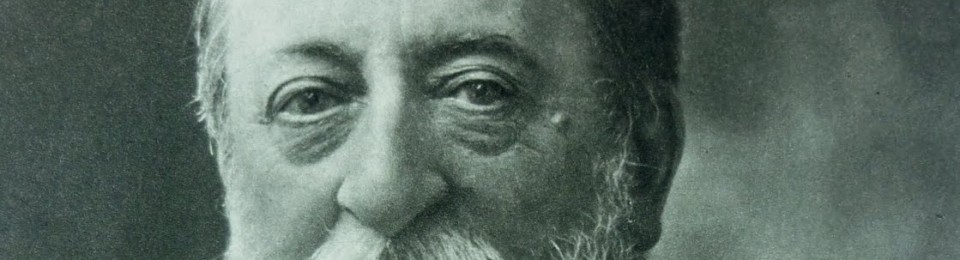

It is in both of these contexts that we can interpret Le Rouet d’Omphale, “The Spinning Wheel of Omphale”, Saint-Saens’ first truly successful venture into the symphonic tone-poem (after things like the Spartacus overture). The legend of Omphale is associated with Hercules, and his being forced by Apollo to work as a slave (dressed as a woman) for Omphale, the Queen of Lydia – and help her at her spinning wheel by holding the wool (though he later becomes her lover). We don’t have to work too hard on Saint-Saens’ subtext for choosing this as a basis for a piece of music, because with a whiff of cheerful misogyny4 he related this in a programme note for the first orchestral performance in 1872 (although a two-piano version was performed in late 1871).

“The subject of this symphonic poem is feminine seduction, the triumphant struggle of weakness against strength. The spinning wheel is only a pretext, chosen only from the point of view of the rhythm and the general appearance of the piece. Those who dig into the details might see at the letter J Hercules moaning in the bonds he cannot break and the letter L Omphale mocking the hero’s vain efforts.”

Clearly, the subtext here is one of nasty female temptresses and how they enslave men. Given Saint-Saens own spectacular (but entirely unsurprising) lack of success with women up to this time, there is more than an element of bitterness here. Interestingly, then, he dedicated the score to the fiercely intelligent and independent French female composer Augusta Holmès – a woman he both admired (and probably lusted after), but also held in some disdain. I suspect she probably rolled her eyes when she read the programme note.

The piece itself is a curious one, consisting of three independent motifs or pieces of melodic material – the first is a stream of fast semiquavers, starting as arpeggios in violins and flute but expanding among the upper strings and clarinet into a buzzy-bee moto perpetuo, clearly representing the endless spinning of the Omphale.

This proceeds into a curiously light skipping and fragmentary tune, somewhat reminiscent of the Dance of the Hours by Ponchielli5.

The tune gets tossed around with fluttering woodwind and some curious off-beat development that would be a challenge to an amateur orchestra (and indeed is for the Orchestre ORTF in the recording below, who have to slow down and slightly re-align to deal with these syncopations). The middle section (letter J in Saint-Saens’ note), is a complete contrast and sounds both menacing a sinister – as if Omphale has suddenly grown a moustache to twirl. For a long time hearing this, I though it sounded like music from a silent movie with a bad guy, a maiden and some railway tracks, so I was somewhat gratified to learn that actually this section of the music was used as the theme music to the 1930s radio adaptation of pulp crime novels of The Shadow. At the climax of this section is the only time in the piece that the relentless spinning of the violins ceases.

But eventually the more light-hearted music returns and eventually spins itself out like an ever thinning and slowing spindle at the end, in what must be one of the quietest and highest endings to a tone-poem (the violins finishing the final couple of notes with high harmonics). Either we’ve left the scene, or Omphale needs to order in some more wool. Either way I think this is a curiously unbalanced piece, which for all its colour doesn’t quite hang together. I don’t dislike it, but I feel a bit like I did after Miss Mottram’s spinning demonstrations.

Le Rouet d’Omphale

Why you might want to listen to it: It does a pretty good job of conveying the relentless spinning wheel and the contrast between Omphale’s teasing and Hercules’ agony.

Why you might want to avoid it: If Saint-Saens were spinning here, I’d say he’d spun a capable jumper, but not quite spun gold. Off with his head.

1 What is never questioned in this story is why on earth she happily marries the king who is quite prepared to kill her if she fails in her ovine pelage alchemy.

2 A failing for which she was not beheaded

3 Presumably this is also why my teacher was Miss Mottram and not Mrs Mottram.

4 Saint-Saens was quite capable of both cheerful and just plain nasty misogyny

5 For those of you familiar with Fantasia, this is the bit with the dancing hippos

Something seems to be missing because I can’t find the footnote 4.

Ooops – you are absolutely right, I failed to copy across about 3 paragraphs in the middle of this. All added back in now!

Pingback: Greatest Hits of the 1870s | The Complete Works of Camille Saint-Saens